Notes From The Honeycomb Hideout is a series of pieces about my life as a child actor

Notes From The Honeycomb Hideout, Part One

Notes From The Honeycomb Hideout, Part Two

In my last installment of NTFTHH, I wrote about the mayhem on the set of the Gino’s commercial, the one and only time the three Munk boys ever worked together, after which I fell into another protracted fallow period and Jonathan — nothing if not consistent — continued what seemed, by 1975, to be a winning streak that had no beginning and knew no end. In our hometown, East Brunswick, New Jersey, my little brother was becoming somewhat of a local celebrity and had begun to obtain the very thing which I had mistakenly but doggedly pursued as my most precious personal goal and the bromide for all of my psychic ills: a public. It turns out that in the end I was actually ahead of my time, anticipating a general turn in popular culture toward the relentless pursuit of celebrity as a spiritual tonic by over twenty-five years, proving that it is indeed possible to be progressive and woefully misguided concurrently.

Jonathan ended 1974 by booking not one but an entire series of commercials for Marx Toys, thereby ensuring that every person in America under the age of thirteen would know who he was. Though they seem beyond quaint to our eyes today, these spots were fairly conceptual for their time: a contemporary, clubhouse-themed riff on the Our Gang comedies of the 192os and 1930s, only without the overt racism that made the original series vaguely discomforting. Toy after toy, commercial after commercial, it seemed like you couldn’t turn on the TV on a Saturday morning without seeing my brother every time Bob McAllister’s Wonderama went to a commercial break: Prop Shot, Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots, Vertibird Rescue Helicopter, and, of course, Marx’s Big Wheel, their biggest selling toy, which, if you’re too young to remember, was a loud, plastic tricycle contraption — essentially a snorting muscle car for the under-ten set. I can still hear the sound of its black, oversized tires shredding the pebbled asphalt of Overhill Road, for this, dear reader, was the sound of my little brother guilelessly skidding across my dreams and that, my friend, is a sound one tries but never succeeds to forget.

Things weren’t going as well for me. From time to time I would get an audition, but I failed to book anything and had to console myself by letting some of Jonathan’s shimmer rub off on me. I hung a huge poster of a caricature of him in Our Gang vintage attire riding a Big Wheel on my bedroom wall. Though you might reasonably jump to the conclusion that I used it as a dart board, I actually found it inspirational, for—in an early example of adaptability and a demonstration of a willingness to embrace reality that generally proved rather elusive—I had begun to look upon Jonathan’s success on TV as a family business and our manager, Dolores Reed, as a “team partner.” Insodoing, I managed to find a point of entry into the narrative of my brother’s burgeoning fame, tangential as it may have been. If Jonathan—a complete natural and ingratiating presence on film—was the one they wanted, not I, then, by gum, I was going to at least be on the winning side somehow! This rather clever coping mechanism allowed me to get through the day without becoming the child they never speak of at the Passover seder: the bitter, overlooked, eldest child who is being eclipsed by his younger brother.

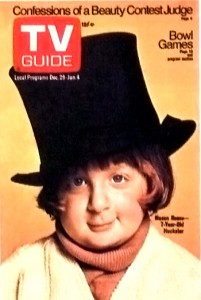

My copious record keeping became newly and happily focused on Jonathan’s exciting batting average, as I watched his column of auditions and booked jobs expand in delightfully impressive proportion. Instead of positioning Jonathan as the enemy, I essentially assumed his identity and made all of his competition the enemy. This was not hard to do because of his aforementioned ambivalence and my aforementioned pushiness. I was, after all, still his older brother. Still a child and in need of an enemy, I chose to demonize poor Mason Reese, the odd-looking, dwarf-like child actor who shot to stardom around this time. He was so popular, in fact, that he published his memoirs and landed on the cover of TV Guide with the caption: “Mason Reese: The Seven-Year-Old Hukster.” I hated his guts. We would see Mason often on auditions because I guess we’d all get sent up for “quirky red-headed kid parts.” When I would run into Mason and his stage-manager mother, I would chat her up, relating to her as a peer and pretending that I was supportive of Mason’s work and happy for his success in order to elevate my own social position.

Me: Oh, hello again Mrs. Reese, hello Mason. I really loved what you did in that Boars Head commercial.

Mrs. Reese: Thank you. You know, that spot was mostly ad-libbed. Mason just made it right up on the spot.

Me: Really? That’s extremely impressive. I also enjoy ad-libbing and recently did quite a bit of it on a little spot my brothers and I did for Gino’s. You wouldn’t have seen it yet because they’re still editing it. Have you been busy lately?

Mrs. Reese: Quite, quite. Mason is just working non-stop.

Me: Jonathan too. How wonderful.

My identity now snugly encased within the armor of my brother’s success, my vitriol toward the unfortunate Reese ebbed in a short story I wrote called “The Great Contest,” wherein I imagined a competition between Jonathan and Mason to see who was the biggest seven-year-0ld actor on the scene. In a curious Freudian switcheroo, I referred to the competition in my story as a quest to decide who was the biggest “seven-year-old hustler,” and I wove the names of all the casting directors and ad agencies I knew of through the tale to give it verisimilitude, name checking BBD&O, Doyle, Dane & Bernbach and Benton & Bowles like they were stores at Brunswick Square Mall. In my story, the contest was decided by a combined grading system of audience applause and a detailed oration of national commercials booked during the previous year. Of course, this being a work of fiction and the sublimation of what my first therapist would describe as “your pathological ambition,” I was able to control the outcome, ensuring that, yes, Jonathan Munk (read “me”), was in actual fact, the winner and the biggest “seven-year-old-hustler” of them all!

In my new role as de-facto personal manager, I no longer had to confront the pesky issue of my own moribund acting career and I could concentrate on the important stuff, keeping Jonathan focused and on-point. When the phone rang and it was Dolores with an audition for Jonathan, I would instantly become the world’s most efficient C-Level assistant, taking down the information with near-Germanic precision, thanking her for hard work on “our” behalf, and then — the tricky part — breaking the news to my brother that he had to go to the city…again. His intrinsic indifference negatively pre-disposed him to each of these work opportunities — the ingrate — and I saw it as my personal responsibility to get him in the right frame of mind so he could win another one for “Family Munk.” It wasn’t temperament on his part as much as a fundamental lack of giving a shit. With my overweening ambition, I had enough “give a shit” in me to motivate the entire adolescent cast of The Waltons with enough leftover to kick Ellen Corby’s ass thirty-five miles to the city and back.

By this time, my mother was a full-time student so she wasn’t much of hindrance to my meddling. To take over the chauffeur job for her so she could study and go to school, she hired a series of people who would chaperone us back and forth to Manhattan via bus. Thus began the Port Authority phase of our adolescence and cleared the way for my “family business” takeover. The first and best chaperone was Deborah Sullivan, the older sister of my dear friend Brigit from up-the-block. Deborah was the first artist I ever knew. A beautiful red-headed young woman with a hot body, usually clad in a scoop-necked bodysuit and tight jeans, everyone just assumed she was my older sister and we had a great time. Deborah did eccentric arty-things, like brush her hair with a dog brush, go to museums, and worry that the three dollars of gas she’d put in her old beater was enough to get her home to New Brunswick. I felt very comfortable with her.

I remember clearly that on Thanksgiving Day 1974, Marx Toys was premiering Jonathan’s commercials during a prime-time airing of the original Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. After our Thanksgiving meal, my entire extended family gathered around the television to watch my brother on TV. Sure enough, there he was! Jonathan appeared in one spot after another: an exaggerated, demonic smile plastered across my face and held tightly, a feat that required so much effort that tears nearly streaked my face from the intense effort required to seem so happy as the family kvelled over my brother. They all agreed that he was a “natural,” and, naturally, I agreed, throwing in an occasional “we” where a “he” should have been.

It was during this period that my mother, attuned to the disparity of fraternal success, echoed my “family-business” strategy and announced that all monies earned from acting would be pooled and put in to a family account. I approved of this decision though I regretted its necessity. Predictably, Jonathan did not seem to mind creating what, at that point at least, could only have been interpreted as a “gift” of his earnings bestowed to his two less prolific brothers in order to keep his oldest brother from completely losing his mind. With a sincere and surprisingly optimistic sweep, mom said that this new system would even out in the end because there would be years where I would be the big earner. I liked the way that sounded, though I wondered where her information actually came from. She had often said she was “smarter than the average bear” but I wasn’t sure that being that smart was as helpful in show business as having whatever mysterious quality that Jonathan had. I am not proud to admit that I wouldn’t have had as sanguine an attitude about sharing the money if the big earner had been myself because, truth be told, though I loved my brothers, I never really got over their existence till much, much later and regarded the very concept of sharing as anathema, except in cases where I was the beneficiary. In fact, according to my mother, I became quite depressed after Jonathan’s birth, allegedly requesting that he be “put in the garbage.” I have every reason to believe the veracity of that comment.

We ended the year, as we’d begun it, celebrating Jonathan’s success. We were invited to a Marx Brothers’ Christmas Party in the Toy Fair building on 23rd and Broadway and my mother, probably fearing the repercussions of another exclusion, made arrangements for me to attend as well. The company wanted to have the new cast running around and playing in their cute little costumes in front of the executives and other muckety-mucks. I stuck close to my mother and step-father and I remember the evening rather warmly, scuttling my negative thoughts, for once, and focusing instead on the occasion of my first grown-up party in New York City. I liked the energy of being out in the city at night in an evening that would in many ways presage so much of my later professional life.

But things were going to get a bit harder for me before they improved.

- Jonathan in a 1974 spot for Marx Toys’ Prop Shot. “Who wins? Not me!”

7 Comments

Comments are closed.