There have long been movies set in a grim, foreboding future. Though I am not immune to the pleasure of seeing our world expressed catastrophically (Metropolis (1927); Planet of the Apes (1968), and Soylent Green (1973) are three favorites that come quickly to mind), in the past decade or so, I have become increasingly irritated that films set in a dystopian future are now the equivalent of an invasive species, cannibalizing the cinematic ecosystem with heartless efficiency, becoming a bloated, cliché-ridden sub-genre in less time that it takes to eat your neighbors arm because there is no more food. Meanwhile, the major studios have pretty much abandoned stories about relatable people, relegating those stories to cable TV. With occasional exceptions, like the first-rate 2009 adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, I am negatively predisposed to visiting the dystopian future, preferring to remain in the dystopian-enough-for-me-present, a world already depleted/scarred/frightened/bleak and hopeless enough. Notwithstanding the foregoing, my deeply held beliefs did not prevent me from accepting a role a few years back in a student film called Standing Still, which was set in a dystopian future where everyone is…covered in bruises.

I am delightfully wretched in my only scene. Though I can be quite effective as myself on-camera, I have not self-identified as an actor since I was a teenager, with good reason. When cast as someone else, it is always a version of my worst self: the disgusted shopkeeper; disgruntled customer; dyspeptic boss; and my favorite, men of great wealth. I have never professed to have depth or range. My role in Standing Still was no different: a robotic federal agent tasked with reassigning Stanley, the titular protagonist, to something that was pretty unclear to me even as we shot the scene. “You’ve been flagged ‘RA-Delta.’ Your residence will be reassigned, as will you,” I inform poor Stanley Still, as my goons swoop in for said reassignment. Though I have fancied the notion of having my own goons since my childhood addiction to the Batman TV series which suggested every star Hollywood’s golden era came equipped with a small, angry posse, I never felt comfortable with dialogue of this sort. No one should ever ask me to utter such a line unless it is the cue for townspeople to emerge singing about RA-Delta and moving the plot forward—preferably far away from me.

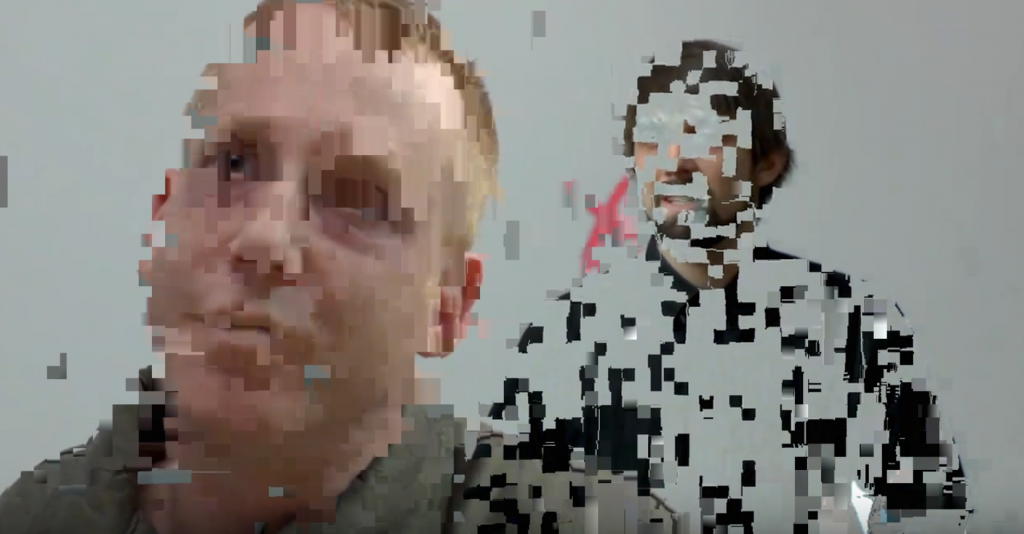

It is somewhat true in general, but certainly in the lazy dystopian future genre, that the plot can make no sense at all because in the dystopian-enough-for-me-present, audiences are primarily focused on the special effects. Pesky problems with story and plot are relegated to the background while things explode at earsplitting volume. This is an inversion of what we see here in the still unfinished Standing Still, where the tape on the walls indicates where special effects were meant to go in post-production. Unfortunately, in movies you can’t put a good script in during post.

Because I am a non-actor—and a rather undisciplined one, at that—I had a hard time handling my seven lines. At the time, I preferred to ascribe my difficulty with the script to a lack of training and having little affinity with the material as opposed to an indication of cognitive disfunction, which had also occurred to me. If memory serves—and it often doesn’t—my anxiety was amplified for having watched a Broadway musical about early onset dementia days before I shot this scene. The name of that show is as remote to me now as the seven lines of dialogue; this too is worrisome.

When I arrived onset I thought I had a loose grip on the text. That’s when my young director gave me blocking and asked me to remember gestures to go with each line of dialogue; I was now officially toast. I found myself unable to remember my lines or the gestures. In three takes I went from my usual officious self to a sweating, hot mess, babbling gibberish and gesturing incoherently while trying in vain to appear cold and powerful. I was woefully out of my element. During some takes, I would blank on everything, so I just typed feverishly on the keyboard with scowl on my face until the director yelled, “Cut!”

I recently found my scene and thought it was too ridiculous not to share. Looking back on my “cameo,” a semantic distinction I prefer owing to the implicit suggestion that I am somebody important doing something important, which is entirely preferable to the reality of being a confused, miscast, actor covered in bruises and perspiration. I am willing to compromise my credibility by reiterating my belief that the most impressive special effect of all is a good script and a well-prepared actor.