“Annie Liebowitz hates me!”

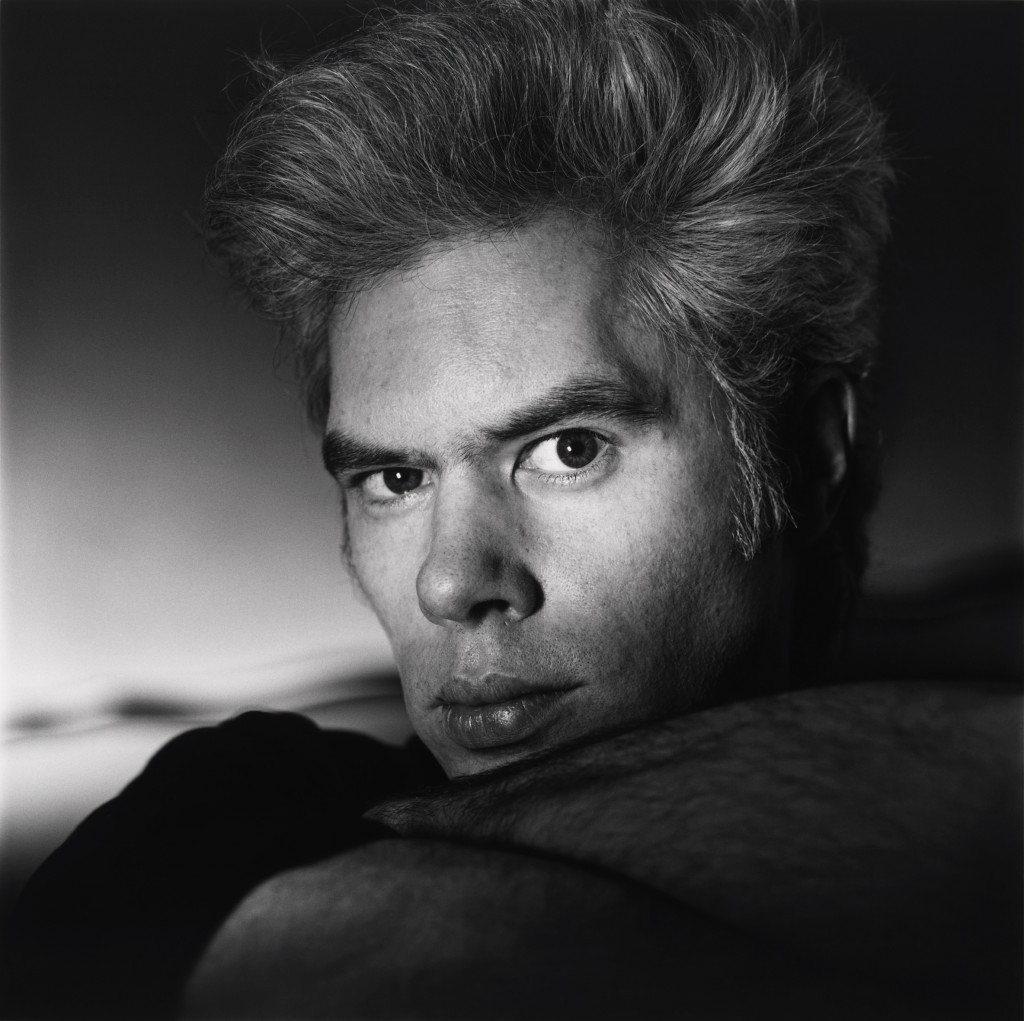

So began my journal entry of May 9, 1986. I was just about to graduate from N.Y.U. and complete a semester-long internship with iconic filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, who was best known for his film Stranger Than Paradise and was then in the process of editing its follow-up Down By Law. Jarmusch was a the very definition of the non-corporate, anti-Hollywood, indie filmmaker. That is, until it came to the help.

As a film production major at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, I was steeped in the New York-centric ethos of the program. A semester away from graduating, I had chosen an internship with Jarmusch in the hope that an apprenticeship with him would give me a meaningful connection or at least teach me something about film. Unfortunately, it didn’t turn out that way, because when it came to teaching his intern something—anything—about cinema, Jim had completely gone Hollywood! Despite my attempts to advocate for any sort of directorial morsel, Jim made it clear that he didn’t want me around the editing room unless it was to “bring him some smokes.” My other primary responsibility was picking up his laundry! Jim’s girlfriend was filmmaker Sara Driver who was also in post-production on a film called Sleepwalk, theoretically doubling my chances to learn. Alas, she went to the same school of mentoring as Jarmusch and was also a heavy smoker with a lot of dirty clothes. They were both nice enough people, just self-centered, downtown artists—essentially Hollywood but with worse hygiene.

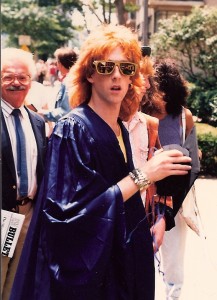

The domestic drudgery of working for Jim lasted six long months. Like a scene from some old Barbara Stanwyck film like Baby Face, I stoically did my menial work and dreamed of getting out that factory town and going to the big city to make my fortune, except I was already in the big city and this wasn’t a movie, just an internship for someone who made them. In a rare example of passivity in my character, I chose to just finish the semester rather than address the issue with the internship department at school. But in the final days of my tenure with the director, Jarmusch finally did do something for me and though it seemed nice in the moment, it turned out to be a really awful thing and, in a scenario that would curiously presage my Rosie O’Donnell kerfuffle ten years later, I found myself squaring off with world-famous lesbian photographer Annie Liebowitz. Here’s what happened, taken directly from my diary:

She was shooting Jim on his roof and I had to go over to his loft to let her in, which I happily did. She knew my name already (which made me feel AWESOME) and seemed friendly too. I wanted to make myself useful so I offered to help them bring all the equipment upstairs which seemed to please her. She even complimented the color of my sweatshirt (a soft baby blue). Everything was going great and I was so happy!

After that I asked Jim if I should split and he, in typical “Jimspeak” mumbled, “no man, hang around here so you can help me out, you know I feel about this.” Jim hates doing press or being photographed. So I went up to the roof and basically worked as a photo assistant, holding a big umbrella to deflect light. I was glad Jim asked me to stay because participating in this shoot was, ironically, the closest I’d been to a film set all semester and a lot more interesting than separating his whites from his colors.

At one point, I asked Annie if she ever shot for Rolling Stone anymore and she said “not in about three years.” She asked me what I did in my “real life.” I told her I was an N.Y.U. student and I was interning for Jim. We finished the set-up on the roof and moved downstairs for another set up. I don’t know where Jim was at that point. While she was setting up the next shot, I heard her say she was moving. “How exciting, where are you moving?” I asked. Well that was it! “Listen to you, upstaging the director!” Everybody laughed and I felt like they were laughing at me. I sheepishly walked away not understanding why she was suddenly so nasty. Had I missed something? I thought to myself, “well at least it was a short rant.” But it wasn’t.

“That’s the problem with interns,” she said to no one in particular, “you don’t pay them. Maybe if you paid them something….”

I was upset and responded, which I think was a mistake. “Listen, I’m not sure what I did, I was trying to be helpful. Sure, maybe I ask a lot of questions but that’s only because I’m interested in your work and I’ve spent the last six months sitting in an empty office and going to the store for cigarettes. It doesn’t matter anyway, this job ends next week.” I hoped she would leave me alone now but she walked right over to me.

“You must be from a wealthy family,” she snapped. I had absolutely no idea what that meant.

“That probably depends on your definition of ‘wealthy’,” I responded. “My parents do okay but we don’t have Annie Liebowitz money!

“Why don’t you leave now?” she said, but cut herself short. Her tone was half-joking, but a second later she addressed the missing half with a singular, dismissive, “really…you can go now.”

I packed up my things as fast as I could and ran downstairs. When I got outside, I paused, leaned against the wall and cried. I felt so small and so confused. I wished I could have explained to her that meeting her was the only exciting thing that’s happened to me all semester. I’m sorry I was so inquisitive, but it’s hard being someone’s slave and never getting any recognition for your creativity.

As I read through this journal entry, almost twenty six years to the day later, I see that Jim asked me to stay and get involved to use me as a human shield—as a way of creating distance between himself and the woman who was trying to peer in to his soul with her camera. It was a lousy thing to do and I wasn’t sophisticated enough to understand how I was being used. All I knew was that I was finally going to watch something interesting and I was like a puppy. Annie Liebowitz was not very nice, it’s true, but her job was to get her shot and though I was deployed by boss, I was a big, inquisitive, red-headed impediment to her goal. I see now that it was Jim who deserved my condemnation, not Annie Liebovitz, and his final act of feeding me to Annie Liebowitz for a snack by using me as a human buffer made the six months of working with him almost cinematic in its symmetry: a complete waste of time.

When I grew up and was lucky enough to have assistants and interns myself, I always thought back to this experience and made sure that I taught them something and that they always got face time with me. I’m proud to have been regarded as a good manager and having given important first jobs to many young people.

You may also enjoy:

John Waters 10 Favorite Overlooked Movies

Jamie Litty

May 7, 2012 at 11:46 amAck! NYU makes me so angry some times. I can’t even say “At least you were allowed to do an internship,” because this one sucked. In contrast, I had lined up an internship at Sixty Minutes and my department chair wouldn’t find a way to do it. The internship was 4 credits and would have put me 2 credits over the maximum # of credit hours that journalism majors could take in the department, which was 36. As a dept chair now myself at another institution, I know that when your student lands an internship with Sixty Minutes, you find a way to make it work! And our students here are NOT allowed to do “janitorial” work as part their 100 hours of labor. It has to be 100 hours of meaningful labor; if they want to clean the bathrooms (or get coffee or whatever) in order to “pay their dues” in the broadcasting business, that’s on their own time!

David Munk

May 7, 2012 at 12:04 pmHi Jaimie, I wish I had you as an internship advisor and not whomever it was. Honestly, the adage that college is wasted on the young is so true. If I could go back and really take advantage of the opportunities that school did provide but with the confidence and wisdom I have now, I’m certain that it could have been so much better. Thanks for taking the time to read and I hope you’ll continue to check out my work. It means a great deal to me. David