One of the beautiful things about the culture of jazz and cabaret music is that life experience, and the emotional deepening that it confers on its artists, is considered an attribute, not a reason to quit. The intimacy of hearing music in a small room is also conducive to one of the primary strengths of a mature singer, or really any singers worth their salt: acting ability. The vanishing art of musical interpretation is all about authenticity and nuance: the gesture of a hand; a raised eyebrow; the artist using the greatest songs ever written to illuminate life’s truths and enable us, the audience, to learn something about ourselves. With the musical experience pared down to its glorious essentials, an hour in a small club with a seasoned legend like the 83-years-young Annie Ross is at once a stroll down memory lane, a tutorial in subtlety, and a master class in the art of the singer as actor.

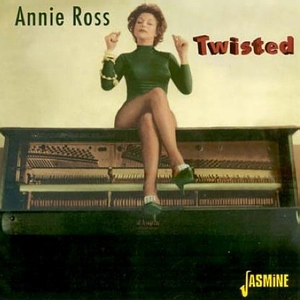

For those of you who are unfamiliar with her place in popular culture, Ross was one third of the seminal jazz vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, who invented the vocalese style, wherein melodic lines usually played by instrumentalists or scatted are, instead, sung with lyrics, the sum effect being a frequently exhilarating and dizzying display of caffeinated wordplay and hipster cool. Perhaps the greatest example of vocalese is Ross’s own 1952 composition Twisted, which set her wonderfully wry lyric about psychoanalysis (another 1950s trope) against an existing melody by sax player Wardell Gray and has since been covered by everyone from Joni Mitchell to Bette Midler.

In addition to her years as a solo artist and with the trio, Ross has also enjoyed an interesting (and most eclectic) career as an actress. From her early roles—she made her film debut singing “Loch Lomond” in Our Gang Follies of 1938 and played Judy Garland’s sister in Presenting Lily Mars (1943)—through later roles in everything from Superman III(1983), Throw Momma From the Train (1987), and, most memorably, Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (1993), Ross has consistently exhibited a unique brand of confidence and self-possession that is still very much on display at the Metropolitan Room.

The night I attended, Ross’s repertoire unfortunately did not include Twisted or any other vocalese. Instead the singer concentrated on a smart set of mostly lesser-known songs by some of the very finest writers of the American standards repertoire—a decision that made good use of her voice. Speaking of her instrument, Ross’s was never a particularly big sound as much as a wonderfully expressive and inventive one, which relied on its outsized personality and unusual effective conversational directness. In that sense, its diminished ability is rather less like an obstacle and more like a later chapter in a long, rich novel.

She was accompanied by a first rate jazz quartet consisting of veterans Neal Miner on upright bass, Tardo Hammer on piano, Jimmy Wormworth on drums, and Warren Vaché on cornet. Not appearing to be a day over 70, and looking smashing in black trousers, black turtle neck and a long black sweater peppered with gold sequins, Ross opened with the up-tempo 1939 Johnny Mercer/Rube Bloom Day In, Day Out, before segueing into a particularly affecting rendition of Rogers and Hart’s 1935 ballad It’s Easy to Remember, which was interpreted with an almost trance-like intensity. A wistful version of the 1941 Tom Adair and Matt Dennis Violets for Your Furs (which included its rarely heard verse) was another highlight that smoothly articulated the singer’s ability to fully inhabit a lyric and tell a story.

Yet another memorable ballad—her forte—was Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer’s I Wonder What Became of Me (1946), a trunk song that she ruefully explained had been cut from their score to St. Louis Woman. One of my favorite numbers was her rendition of Ooh-Shoo-Be-Doo-Bee (Dizzy Gillespie, Bill Graham, Joe Carroll), performed as a playful duet with charismatic sideman Vaché, which served as a sort of musical counterpoint to her closing song, One Meatball (Hy Zaret, Lou Singer, Charles Martin Lane). In talking about the latter piece, she acknowledged its original recording in the 1940s by Josh White (which, incidentally became the first million-selling record by a black man). It seems appropriate that Ross finished with a song associated with an African-American because as a jazz artist and the person I would personally nominate as the “Queen of the Hipsters,” Ross’s own musical- and personal history has been so thoroughly reflective of and accepted by black culture. (Indeed, Lambert, Hendricks and Ross was a multi-racial group at a time when that was almost totally unheard of).

Yet another memorable ballad—her forte—was Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer’s I Wonder What Became of Me (1946), a trunk song that she ruefully explained had been cut from their score to St. Louis Woman. One of my favorite numbers was her rendition of Ooh-Shoo-Be-Doo-Bee (Dizzy Gillespie, Bill Graham, Joe Carroll), performed as a playful duet with charismatic sideman Vaché, which served as a sort of musical counterpoint to her closing song, One Meatball (Hy Zaret, Lou Singer, Charles Martin Lane). In talking about the latter piece, she acknowledged its original recording in the 1940s by Josh White (which, incidentally became the first million-selling record by a black man). It seems appropriate that Ross finished with a song associated with an African-American because as a jazz artist and the person I would personally nominate as the “Queen of the Hipsters,” Ross’s own musical- and personal history has been so thoroughly reflective of and accepted by black culture. (Indeed, Lambert, Hendricks and Ross was a multi-racial group at a time when that was almost totally unheard of).

Speaking of the singer’s history, if the evening had a flaw, it was that it was simply not possible for the audience not to feel shortchanged in the storytelling department by Ross’s disinclination to tell very much. The one anecdote she shared, about Nat “King” Cole and Verve president Norman Granz, to set up Mack Gordon’s This Is the Beginning of the End, was riveting. Considering that her life has included everything from personal connections with every significant jazz musician of the mid-20th century to starring roles in classic B-horror films like Basket Case 2 and Basket Case 3: The Progeny, I longed to hear more. In this regard, Annie Ross is very much a jazz singer and very much not a traditional cabaret artist; there was no imperative for patter whatsoever, only for the intrinsic quality of the songs and their performance to measure up to the singer’s exacting standards of good taste. And in that regard, at the age of 83, Miss Ross still delivers the goods.

This review first appeared on the bistroawards.com website

You may also enjoy:

Painful Corners: The Time I Was a Cabaret Singer For One Night

Torch Song Elegy, Volume One: The Man That Got Away—How The Loss of a Generation of Gay Men Affected Our Ears as Well as Our Hearts

10 Comments

Comments are closed.